Is Hydropower Available In The Midwest?

Hydropower, or hydroelectric power, is a renewable energy source that utilizes the natural flow of water to generate electricity. It works by using the kinetic energy from falling or fast-moving water to turn large turbines that are connected to power generators. Hydropower is considered “renewable” because it relies on the water cycle, which is continuously replenished by the sun.

The Midwest region of the United States, often referred to as the Midwest, includes the states of North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, Indiana, and Ohio. This region has access to major waterways including the Mississippi River, Missouri River, Ohio River, and the Great Lakes, providing potential opportunities for hydropower generation.

With abundant water resources and existing dams, the Midwest has the capability to generate clean, renewable electricity through hydropower projects both large and small. However, only a fraction of the hydropower capacity in the Midwest has been developed so far.

Hydropower Basics

Hydropower is a form of renewable energy that converts the energy from flowing water into electricity. It works by using a dam to store water in a reservoir. When the water is released from the reservoir, it flows through a turbine, which spins a generator to produce electricity. There are three main types of hydropower facilities:

Impoundment – This type uses a dam to store river water in a reservoir. Water released from the reservoir flows through a turbine, spinning it, which in turn activates a generator to produce electricity. Impoundment facilities allow electricity generation to match electricity demand by controlling water release through the turbines (Source: https://www.energy.gov/eere/water/types-hydropower-plants).

Diversion – A diversion facility channels a portion of a river through a canal or penstock, spinning a turbine to produce electricity without the use of a dam or impoundment. They operate by the force of the river flow alone (Source: https://www.dsoelectric.com/hydropower).

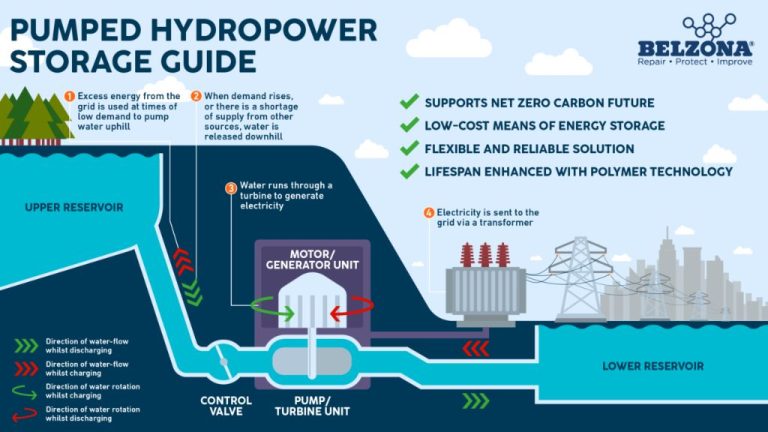

Pumped storage – During periods when electricity demand is low, surplus electricity from the grid is used to pump water from a lower reservoir to an upper reservoir. During periods of high demand, the stored water is released back down into the lower reservoir through a turbine to generate electricity (Source: https://www.energy.gov/eere/water/how-hydropower-works).

Hydropower Potential in the Midwest

The Midwest region contains abundant water resources that provide potential for hydropower generation. The region contains portions of the Great Lakes, including Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, and Lake Erie, which comprise the largest system of fresh surface water on Earth EPA. Major rivers in the region include the Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, Illinois, and Saint Croix Rivers. The Illinois Waterway connects Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River via rivers, lakes, and canals Water and Land of the Midwest.

The abundance of water resources and elevation changes provide opportunities to generate electricity from hydropower by capturing the energy from flowing water. However, hydropower potential depends on factors like stream flow rates, reservoir storage capacity, and feasibility of dam construction.

Existing Hydropower Facilities

Several major hydropower facilities already exist in the Midwest region. Some of the largest include:

The Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River in Washington is one of the largest hydropower facilities in the United States, with a generating capacity of 6,809 megawatts. Construction was completed in 1942. (List of hydroelectric power stations in the United States)

The Chief Joseph Dam, located on the Columbia River on the border of Washington and Oregon, has a generating capacity of 2,620 megawatts. It was completed in 1958. (Missouri River Hydropower – USACE Omaha District)

The Robert Moses Niagara Hydroelectric Power Station in Lewiston, New York has a generating capacity of 2,755 megawatts. It was originally built in 1961. (Midwest)

These massive facilities demonstrate that hydropower infrastructure can be successfully implemented in the region. Many other medium and large scale hydropower plants exist as well.

Regulatory Environment

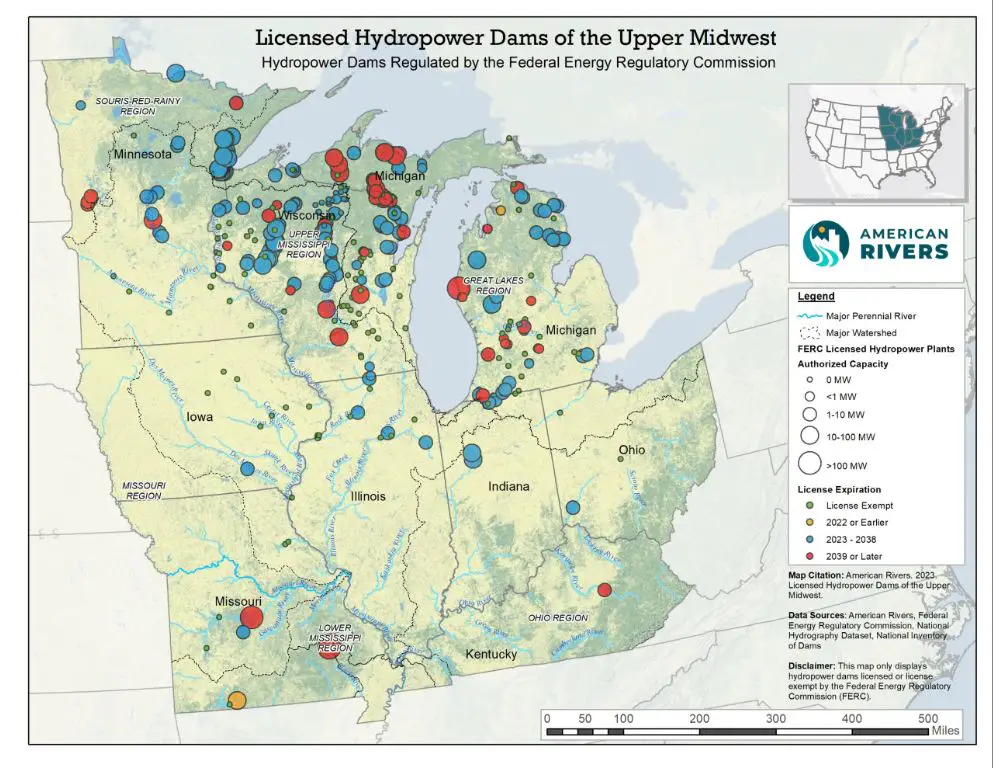

Hydropower projects in the Midwest are regulated at both the federal and state level. At the federal level, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has authority over non-federal hydropower projects located on navigable waterways or federal lands, or connected to the interstate electric grid https://www.ferc.gov/industries-data/hydropower. FERC issues licenses for these projects, which typically last 30-50 years. The licensing process involves environmental reviews, public input, and tribal consultations.

For non-FERC regulated dams, state policies come into play. In Wisconsin for example, the Department of Natural Resources regulates non-hydro dams through requirements for inspections, repairs, increased spillway capacity, and potential removal https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/dams/hydroElectric.html. States may also have policies regarding permitting, public access, and environmental protections at hydropower facilities.

Recent federal policy changes include the Hydropower Regulatory Efficiency Act of 2013, which aimed to streamline the FERC permitting process for certain qualifying facilities. There are also periodic regulatory updates, such as FERC’s July 2023 notice soliciting input on two proposed hydropower projects in the Midwest https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/07/26/2023-15844/midwest-hydro-llc-sts-hydropower-llc-notice-soliciting-scoping-comments.

Environmental Considerations

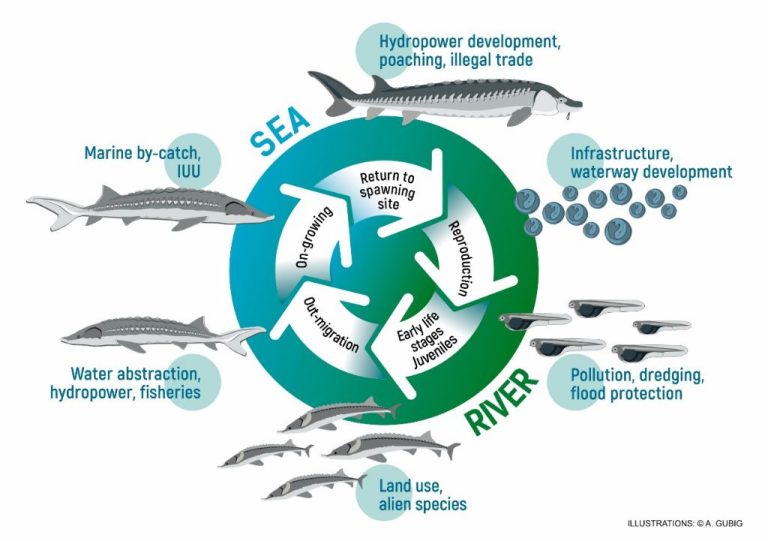

Hydropower can have significant impacts on wildlife and ecosystems. The dams used for hydroelectric power generation often obstruct fish migration and disrupt natural water flows. As a result, fish populations can decline or even disappear from rivers dammed for hydropower. Dams also flood large areas of land, destroying habitat for terrestrial animals and vegetation (Erwin Record, 2023).

The flooding of land for reservoirs leads to decomposition of plants and trees that were previously living there. As this plant matter decays underwater, it releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Some researchers have found that certain hydropower reservoirs can have a higher greenhouse gas impact per unit of energy than fossil fuel power plants. However, these findings are debated, as other reservoirs may emit less greenhouse gases (Grist, 2019).

Overall, the environmental effects of hydropower must be carefully evaluated for each location. With proper planning and mitigation strategies, some impacts can be reduced, such as providing fish passageways on dams. But in certain sensitive ecosystems, the ecosystem disruption caused by dams may be judged to outweigh their benefits.

Economic Viability

The economic viability of hydropower in the Midwest depends on weighing the costs and benefits. On the cost side, building new hydropower dams and retrofitting existing dams requires major upfront capital investments. The region’s relatively flat terrain means facilities may require substantial civil engineering works to create sufficient hydraulic head. Maintenance and operations costs must also be factored in over the project lifespan.

However, once built, the “fuel” for hydropower is free and renewable, providing a long-term source of clean electricity at a relatively stable cost. Hydropower facilities also last for decades, allowing capital costs to be spread over many years of operations. There can be opportunities to generate additional revenue from recreational activities at reservoirs. Furthermore, the avoided costs of carbon emissions and air pollution provide economic benefits compared to fossil fuel power plants.

Each potential hydropower site has its own cost-benefit considerations that must be evaluated. Overall, hydropower can be economically attractive in the right locations, but high initial development costs pose a challenge to widespread deployment in the Midwest.

Public Opinion

There is broad public support for hydropower in the Midwest. According to the National Hydropower Association, Americans view hydropower as a clean, reliable and renewable resource, and support hydro-specific initiatives for development (https://www.hydro.org/waterpower/why-hydro/broad-public-support/). In Michigan specifically, there was enough public support to motivate a public agency to purchase three small hydropower plants from their private owner in order to guarantee consistent water levels (U.S. Hydropower Market Report).

However, some environmental groups have expressed concerns about the impact of dams on river ecosystems and fish populations. There is debate around whether new hydropower development is compatible with river restoration efforts. Public opinion likely depends on the specific project location and design.

Future Outlook

The potential for growth in hydropower in the Midwest region is significant. According to the U.S. Hydropower Market Report, the Midwest has ample untapped hydropower resources that could potentially generate over 17 GW of additional capacity [1]. Several factors point to future growth opportunities:

- Existing dams that could be retrofitted for hydropower – There are over 2,500 non-powered dams in the Midwest that could potentially be retrofitted to generate electricity.

- New small/low-impact hydropower – Smaller hydropower projects of under 30 MW capacity on existing infrastructure like canals, pipelines, and small streams could provide distributed renewable energy.

- Pumped storage hydropower – The Midwest’s terrain and abandoned mines provide opportunities for additional pumped storage facilities to support grid reliability.

- Supportive policies – State renewable portfolio standards and federal incentives can encourage more hydropower deployment in the region.

However, challenges like high costs, regulatory hurdles, and environmental concerns must also be addressed. But with the right policies and strategies, hydropower generation in the Midwest could see significant growth in the years ahead.

Conclusion

In conclusion, hydropower has significant potential in the Midwest region due to the availability of rivers and reservoirs that can support hydropower facilities. While hydropower currently provides only around 3-6% of electricity in most Midwestern states, there is room for growth, especially from small, low-impact hydro projects. Existing large-scale facilities on major rivers demonstrate that large hydropower can work in the Midwest climate and geography. However, building new large dams faces environmental concerns and high costs. Smaller run-of-river projects may provide a middle ground, avoiding damming major rivers while still utilizing the energy potential of smaller waterways. Economic viability depends heavily on regulatory incentives and electricity prices. Overall, hydropower could likely supply over 10% of the Midwest’s renewable energy needs in the coming decades with the right policies in place. More studies are needed to fully understand the scale of economically and environmentally sustainable hydropower potential across the region.